It

was

a

breakthrough

moment

for

BW

senior

Juan

Pablo

Taborda

Bejarano

'22

as

he

took

the

next

step

in

his

research

project

and

traveled

to

the

University

of

Southern

California

to

focus

on

the

effect

consuming

artificial

sweeteners

in

childhood

has

on

taste

later

in

life.

It

was

a

breakthrough

moment

for

BW

senior

Juan

Pablo

Taborda

Bejarano

'22

as

he

took

the

next

step

in

his

research

project

and

traveled

to

the

University

of

Southern

California

to

focus

on

the

effect

consuming

artificial

sweeteners

in

childhood

has

on

taste

later

in

life.

For the neuroscience-biology major, it was a pinnacle experience that brought together his four years of undergraduate study with his career goal. It was a journey that started in his hometown of Bogotá, Colombia, and spanned 2,583 miles to BW.

As Taborda Bejarano prepares to graduate in May and attend the Medical College of Wisconsin to pursue a Ph.D. in neuroscience, he is one example of how BW's hands-on approach to research enables aspiring graduate and medical school students to receive acceptance at top universities.

The prestigious opportunity began his first year at BW when he became a lab assistant for Dr. Clare Mathes, department chair and associate professor of neuroscience. He worked on a project alongside Mathes and neuroscience students Gaurikka Mendiratta '21 and Delenn Hartswick '21 to determine if drinking artificial sweeteners in childhood has an effect on taste-based behavior that lasts into adulthood.

Upon

the

graduation

of

Mendiratta,

who

is

now

in

her

first

year

of

medical

school

at

the

University

of

Limerick,

Ireland,

and

Hartswick,

who

is

pursuing

a

Ph.D.

in

neuroscience

at

Georgia

State

University,

Taborda

Bejarano

continued

and

expanded

the

research

as

a

BW

summer

scholar

in

2021

and

later

for

independent

thesis

work.

Upon

the

graduation

of

Mendiratta,

who

is

now

in

her

first

year

of

medical

school

at

the

University

of

Limerick,

Ireland,

and

Hartswick,

who

is

pursuing

a

Ph.D.

in

neuroscience

at

Georgia

State

University,

Taborda

Bejarano

continued

and

expanded

the

research

as

a

BW

summer

scholar

in

2021

and

later

for

independent

thesis

work.

Through Mathes, he connected with Dr. Lindsey Schier of the department of biological sciences at the University of Southern California, a top-tier research school. Schier's lab focuses on how the chemical constituents of foods and fluids are sensed, processed in the brain and channeled to behavioral outputs. Mathes and Schier, who have similar research interests, have been collaborating since 2018.

During winter break of this year, Taborda Bejarano traveled to Los Angeles to further his research in Schier's lab. The trip was funded, in part, by an external grant from Nu Rho Psi, the National Honor Society in Neuroscience, which was awarded to Taborda Bejarano. It was a monumental experience both personally and professionally for Taborda Bejarano.

"My

goal

for

this

experience

was

to

learn

new

techniques

and

further

my

real-life

experience

about

how

a

lab

functions.

I

now

know

what

a

research-driven

institution

looks

like,"

he

explained.

"My

work

in

the

lab

of

Dr.

Schier,

our

collaborator,

was

exciting

because

my

objective

after

graduation

is

to

go

to

graduate

school

and

continue

doing

research

in

a

professional

manner."

"My

goal

for

this

experience

was

to

learn

new

techniques

and

further

my

real-life

experience

about

how

a

lab

functions.

I

now

know

what

a

research-driven

institution

looks

like,"

he

explained.

"My

work

in

the

lab

of

Dr.

Schier,

our

collaborator,

was

exciting

because

my

objective

after

graduation

is

to

go

to

graduate

school

and

continue

doing

research

in

a

professional

manner."

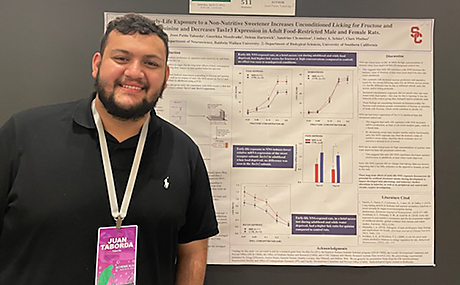

His time in the lab was a success. Not only did it correlate to top-level graduate work and have consequential findings, but Taborda Bejarano will present his research at the national conference of the Association for Chemoreception Sciences this month (with Mendiratta and Hartswick as authors). The team also hopes to submit the work for peer-reviewed publication in a scientific journal.

Mathes, who studies the link between taste-based physiology and behaviors, is hopeful that Taborda Bejarano's findings could lead to real-world application that can affect dieticians, nutritionists and families.

"A

lot

of

research

suggests

too

much

sugar

isn't

good

for

kids.

It

can

lead

to

weight

gain

and

even

obesity,

increase

tooth

decay,

and

it

may

even

contribute

to

poor

attention

and

memory

issues

that

last

into

adulthood,"

stated

Mathes.

"A

lot

of

research

suggests

too

much

sugar

isn't

good

for

kids.

It

can

lead

to

weight

gain

and

even

obesity,

increase

tooth

decay,

and

it

may

even

contribute

to

poor

attention

and

memory

issues

that

last

into

adulthood,"

stated

Mathes.

"Diet beverages, which contain no sugar, get their sweetness from non-nutritive artificial sweeteners. These additives work on taste buds in a way similar to nutritive sugar, so our brain tells us, 'this tastes sweet,'" she said.

"While having kids drink beverages that contain artificial sweeteners prevents them from consuming sugar, we don't know the effects those artificial sweeteners might have later in life when those former children choose for themselves what to eat and drink," Mathes pointed out.

"For example, we wondered what an adult might be more likely to drink if, as a kid, that person only had diet beverages. Our study suggests, at least in a non-human model, that consuming artificial sweetener daily during childhood and adolescence might make fructose seem super tasty once adulthood is reached," continued Mathes.

"Juan's work in Dr. Schier's lab took our behavioral findings a step further as he found that drinking artificial sweeteners daily resulted in decreased levels of one of the elements in taste buds needed to taste sweetness," she noted.

"To put that in human context, this might mean that drinking a lot of artificial sweeteners as a kid might change how their taste buds work, such that when these kids grow up, they like sugar even more," she explained.

"If

we

look

at

dietary

and

nutritional

considerations,

then

perhaps

adults

who

like

sugar

more

than

normal

would

be

more

likely

to

consume

greater

quantities

of

it

and

could

experience

potential

detriments

like

obesity.

For

families,

perhaps

the

take-home

message

of

this

research

is

that

giving

kids

water

to

drink

instead

of

diet

beverages

or

sugared

drinks

might

be

the

safest

course

of

action,"

she

concluded.

Note: According to The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education®, an R1 school is a doctoral University with very high research activity.