What would Northeast Ohio's forests look like if we could take a time machine back to the turn of the 19th century before settlers arrived? How have the forces of urbanization changed the landscape from 1800 to now? What should restoration goals for the county's carefully preserved "Emerald Necklace" park system look like in the future?

A

BW

biology

professor,

Dr.

Kathryn

Flinn,

and

junior

BW

biology

major

Tylor

Mahany

'19,

dug

into

those

questions

through

"witness

tree"

research

that

relies

on

observations

recorded

in

handwritten

field

books

from

the

area's

very

first

land

surveys.

A

BW

biology

professor,

Dr.

Kathryn

Flinn,

and

junior

BW

biology

major

Tylor

Mahany

'19,

dug

into

those

questions

through

"witness

tree"

research

that

relies

on

observations

recorded

in

handwritten

field

books

from

the

area's

very

first

land

surveys.

Meticulous maps and analyses of such records at the Western Reserve Historical Society were compared to a more recent survey of forestland completed by Dr. Constance Hausman, a plant and restoration ecologist with the Cleveland Metroparks.

The

findings,

just

published

in

the

international

Journal

of

Vegetation

Science,

show

tremendous

changes

in

the

region's

plant

communities

over

the

past

200

years.

Back

then,

the

area

was

94

percent

forested

with

most

woodlands

dominated

by

beech

or

oak

trees.

Most

of

the

remaining

areas

were

covered

by

wetlands.

The

findings,

just

published

in

the

international

Journal

of

Vegetation

Science,

show

tremendous

changes

in

the

region's

plant

communities

over

the

past

200

years.

Back

then,

the

area

was

94

percent

forested

with

most

woodlands

dominated

by

beech

or

oak

trees.

Most

of

the

remaining

areas

were

covered

by

wetlands.

By 2014, development had swallowed up half of the wetlands and reduced forested areas in the county to less than 20 percent. Maple, elm and cherry trees, which bounce back easier and faster after disturbances, have replaced many of the once-dominant native trees, and the region's vegetation has become more homogeneous, losing much of its original variety.

The records also suggest a lack of permanent Native American settlements in the area at the time, with just one Indian "sugar camp" noted, and offer no evidence of vegetation shaped by frequent fire.

Flinn

says

this

type

of

study,

which

reveals

a

"gold

mine"

of

information

about

how

past

land

use

choices

have

impacted

natural

plant

habitats,

helps

to

predict

the

likely

consequences

of

future

urban

development.

Flinn

says

this

type

of

study,

which

reveals

a

"gold

mine"

of

information

about

how

past

land

use

choices

have

impacted

natural

plant

habitats,

helps

to

predict

the

likely

consequences

of

future

urban

development.

"Understanding how plant communities change over time is important to consider when we think about protection and restoration of natural ecosystems," says Flinn. "Many ecologists have mined early land survey records to help inform restoration goals, but this type of mapping had never been done before in Cuyahoga County."

One takeaway from the data? "Conservationists might explore future land acquisitions with beech and oak forests," Flinn notes. "Those types of additions would make protected parklands more representative of the pre-settlement era when half the forests were dominated by beech trees and a third were oak."

Flinn and Mahany teamed up to start the research during their first semester on campus. Mahany was a freshman in the newly appointed Flinn's biology class.

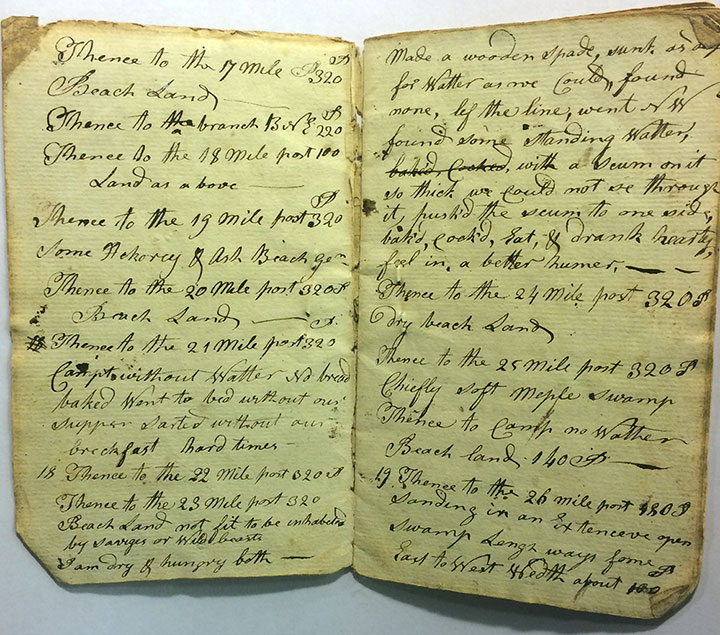

"It took a lot of detective work and perseverance on Tylor's part to locate and decipher the surveyors' line-by-line observations," Flinn explains. "Some of the private Connecticut Land Company survey records held at the Western Reserve Historical Society were on microfilm; others were in handwritten, hand-sewn journals from the 1700s."

The

survey

notes

painted

a

vivid

picture

of

the

surveyors'

daily

adventures

as

they

navigated

the

wilderness

of

northeast

Ohio,

crossing

swamps

and

thickets

"as

thick

set

as

the

hair

on

a

dog's

back,"

battling

diseases,

snakebites,

gnats

and

mosquitoes,

and

hunting

for

meat.

The

survey

notes

painted

a

vivid

picture

of

the

surveyors'

daily

adventures

as

they

navigated

the

wilderness

of

northeast

Ohio,

crossing

swamps

and

thickets

"as

thick

set

as

the

hair

on

a

dog's

back,"

battling

diseases,

snakebites,

gnats

and

mosquitoes,

and

hunting

for

meat.

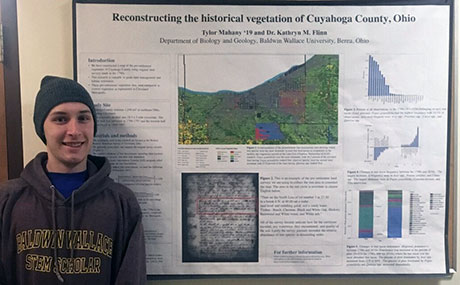

Mahany, who recently presented the findings at the 2018 Ohio Natural History Conference, adds, "The detail that the surveyors went into about the trees, soils and land was amazing. I learned a lot about the power of field observations, and how they could be useful centuries later."

Flinn is scheduled to present the research at two public forums in the fall: